Will the legacy and collecting favor of the Brooklyn Dodgers last or become a baseball memory row of apartment buildings like its old home: Ebbets Field? Focusing directly, we’re talking about the Brooklyn Dodger team(s) from 1947 to 1956 which left an indelible impression on not only baseball but on the nation in that decade.

The impact of this impressive baseball assembly came during an early start to the cold war — post 1946. It was a Dodger team classified as one of the greatest and most exciting teams of baseball covering a10-year span that would include six World Series appearances. Most of the earlier Brooklyn Dodgers past remains obscure to most fans and collectors. After 1957, there was no more Brooklyn Dodgers. The team escaped its borough to the broader western expansion of Los Angeles.

Today Brooklyn Dodgers memorabilia still remains sought after but as its loyal fans grow older or pass away will that interest fade away, like those potential buyers of deceased icons like Joe DiMaggio (where have you gone?) Ted Williams or even Stan “The Man” Musial?

There are those who believe the immediate postwar Dodgers of that era will always have a staple buying and collecting public for those magical Brooklyn nines.

Strangely, if you asked casual baseball fans if they knew much about the Brooklyn Dodgers before 1940, they would have scratched their head. Frankly, not many baseball aficionados paid much attention to the Dodgers before 1947? The team was in only two World Series and lost both of them (1916 and 1920).

Names like Zack Wheat, manager Wilbert Robinson or the colorful “Dazzy” Vance might spring up from a lack luster history of pre-1940 Dodgers teams. From the beginning of their existence, the Dodgers hum- drummed their way through decades of forgettable seasons.

However, in the late 1930s, there was light at the end of the Brooklyn tunnel.

The man who began rubbing two sticks together to fire up the franchise was none other than Larry MacPhail, a promoter extraordinaire, who once was said to have planned to capture the Kaiser in World War I and who, as general manager of the Cincinnati Reds in 1938, brought night baseball into the big leagues.

To say MacPhail was brilliant but erratic would be putting it mildly. Drinking bouts would bring about problems and his downfall in many cases with the Dodgers and later with the New York Yankees.

But shortly after he arrived in Flatbush MacPhail stirred some life into the moribund Dodgers, introducing night baseball and radio to Brooklyn and — lo and behold — even fielding some decent players

MacPhail’s team even managed the National League pennant in 1941 with fine young players like Pee Wee Reese, Dolph Camili and the talented but unlucky Pete Reiser. World War II took away both MacPhail and Brooklyn’s chances for further pennants. Branch Rickey would become the new Dodger general manager. The Dodgers also became the first major league team to draw one-million fans through their turn styles. This would be a trend that would continue to get better.

It would be Rickey’s teams and personnel who would win a remarkable six National League pennants beginning in 1947 and narrowly miss two more in last game season losses.

Alas, as great as these teams were, they could only win one World Series, having to match up with the seemingly unconquerable New York Yankees who would frustrate them in 1947, 1949, 1951, ’52, ’53, and 1956, successes snapped only by Brooklyn’s triumph in 1955. Despite all of its domination of the National league from 1947 to 1956, losses in the series to the crosstown rival Yankees, Dodgers fans always seemed to be wailing, “Wait ‘till next year.”

The flash of brilliance and boldness that put this Brooklyn organization on the baseball map forever was Rickey’s signing of the major league’s first Negro player and a catalyst for the team: Jackie Robinson, a dynamo and personality who left an enduring influence on the game. The astute Rickey surrounded him with a superb cast: Reese, who had arrived in Brooklyn much earlier and along with Hall of Famers like Roy Campanella, Duke Snider, and star players like Gil Hodges, Don Newcombe, Carl Furillo and Carl Erskine. These Dodgers would be immortalized by Roger Kahn’s epic book on the team: “The Boys of Summer.”

Only three teams would interrupt those Dodger pennant hopes during that cold-war 1947 to 1956 span and those came in agonizing ways like the narrow final-game loss to the 1950 Philadelphia Phillies and to the 1951 New York Giants who came from behind 13 1/2 games to force a playoff in 1951 ending in the Giants’ Bobby Thomson epic homer victory.

It would be Rickey, who by developing a broad farm system of talent and trades, would create these happy fruits of achievement rivaling only that of the omnipotent rival Yankees.

It would be the threshold year of 1947 that would become not only a milestone of the first Afro-American in baseball resulting in the national controversy that would swirl around that momentous event but it was also the start of the Brooklyn Dodger dynasty that would last for the next decade.

Ironically the general managers of the two teams squaring off in the 1947 World Series would be: MacPhail who had also joined the Yankees also as a part owner and Rickey now heading the Dodgers, a position he took when MacPhail enlisted in the service (1942) in World War II.

The Dodgers futility against the mighty Yankees in World Series after World Series, but also its great successes in dominating the National League stamped the team indelibly in many fans’ minds. Importantly black baseball fans now could love a major league team to follow and cheer for but the Dodgers appeal went beyond that, perhaps even embracing fans who were struck with the agonizing close season-ending losses.

If MacPhail was an innovator and idea man, his successor with the Dodgers, Branch Rickey, was of the same mold but in a far more methodical and controlled vein that the mercurial MacPhail. And Rickey brought with him the revolutionary major league concept of a farm system where multitudes of young players would be signed and controlled through teams with working contracts with his former team, the St. Louis Cardinals.

Besides the solid nucleus of iconic stars Rickey would pump his teams with a continuous flow young stars like Carl Erskine, Johnny Podres, “Junior” Gilliam, Charlie Neal, Johnny Roseboro or trade for players like “Preacher” Roe and Andy Pafko.

Though the 1941 Dodger-Yankee clash was the first meeting the crux of the heroic rivalry seemed to begin in 1947 when the cross-town foes began spreading national attention electronically and into historic numbers of homes with radio and emerging television (the 1947 World Series would become the first televised). In seven tough games, the Yankees clinched the first series match-up between the two teams in the start of what would become a long-lasting rivalry.

It would furnish the denizens of Brooklyn to begin their chant of “Wait ’til next year!” But the Yankee bats and arms would dominate in 1949, 1952 and 1953, until, finally, “next year” CAME with Brooklyn prevailing over the Yankees in seven games to win their only World Series in Brooklyn. A grudge re-match would occur in 1956 with the Dodgers struggling through seven games though suffering the ironic fate of losing to Don Larsen when he pitched a perfect game, the only one in World Series history. By 1958 it was all over for not only the magic of the close competition but for the Dodgers in Brooklyn. Its owner, Walter O’Malley, looking west for more attractive financial environs took the team to Los Angeles.

But the Brooklyn Dodgers of that time seemed to leave an indelible footprint on the American psyche. Or so, it has seemed. Some of the Dodger stars like Hodges, Snider went to the West Coast and Gilliam seemed to last the longest but three of the later arrival pitchers: “Sandy” Koufax, Don Drysdale, and Johnny Podres, the hero of the 1955 Dodgers win, would extract a sweet revenge in the 1963 series against the Yankees by sweeping New York in four tilts.

An overriding question remains, which along with the gradual fading of those super stars of the 1940s and ‘50s like Joe DiMaggio, Ted Williams and Musial in the memories of collectors will the Dodger magic still continue to imprint with younger collectors? This might be true no. What has helped recently to create a new surge of interest has been a movie release on Jackie Robinson.

Frank Graham Jr. who was Dodger publicist during this and author of “Farewell to Heroes,” offers his thoughts on the Brooklyn Dodger permanence.

“I think the mystique of the Dodgers will survive, perhaps more than any other in the game. In fact, the period it covers is a long one–going back to the daffiness days in the thirties, the continued “disasters” as the team’s fortunes changed (the Mickey Owen flub, the Bobby Thomson bomb) in the forties and early fifties, and then the “boys of summer” in the mid-fifties.

And remember, the latter was celebrated in a book of consequence. That’s almost 25 years! There were elements like the dramatic integration and the tightly knit community. I don’t think any other “dynasty” compares. The new Jackie Robinson documentary that Ken Burns will produce next April is a part of the continuing celebration.

Though the concept of team collecting has been around in the baseball hobby for years in cards and autographs, this fad spread to the baseball collecting community as well.

Master glove collectors like John Graham and Roy Anderson in Dallas, along with Bob Gray in Virginia began their assemblies of Dodger player glove collections concentrating on the key post-war era.

One of the key and extremely rare player gloves and highly sought was a USA made Jackie Robinson glove and two of these were nabbed by Anderson as keystones of his glove collections. Another tough one was that of “Junior” Gilliam and Graham admits he spent a lot of time trying to track that one down. A devoted glove collector Graham, who was an original co-founder of baseball ballqube baseball displays, made one of his side collecting goals –besides that of acquiring Hall of Famer and antique gloves — acquiring the player model gloves of the Dodgers.

“Dad was a Yankee fan when I was growing up and after the 1955 Dodger World Series win in 1955 we had a natural rivalry going. I was totally smitten with the Dodgers the next year.

“I got into baseball card collecting and first thing in the mornings I would check the box-scores paying particular interest to Duke Snider and Don Newcombe. On the weekends my dad and I watched the game of the week and when the weather was bad I would listed to the game of the day on the radio. I was happy when the Dodgers were on TV or radio.

“In the mid-1960s I was in Santa Ana, Ca. in the USMC and quite often caught a game on TV or radio and particularly remember the great announcer of Vin Scully

“Early 80’s I really got interested in baseball cards. My son got me into it. We had a bunch of the cards and cards set. At one time I had all of the Duke Snider cards except for the Hires Root Beer card. In the late 1980s I fell in love with baseball gloves, got rid of most my cards and the rest is history.”

Besides the Dodgers Anderson tuned his collection, including gloves, to particularly Jackie Robinson and the Negro League players.

Anderson, law professor at SMU, grew up living across from a ballpark in Alexandria, La., home of the Alexandria Aces.

“I remember listening to the radio at night when I was about five years old. They kept mentioning this guy Joe DiMaggio every other sentence it seemed like.

“The Aces were playing across the field from home. I thought that was the game I was listening to. Some guy named Joe just across the city park.

“But, thank goodness, I did not grow up a Yankee fan. The Aces were real low minor league, but they had some affiliation with the Brooklyn Dodgers – Duke Snider was the Aces manager for a year. So, instead of the Cardinals game, which most cities in the area got, we got the Dodgers.

“From age 10 we played baseball in the little league park which was also across from our home from morning until dark dang near every day. I had a little transistor radio, which we kept in the dugout. Dodgers games playing in the background.

“I was Duke Snider though I bat right and never could jump. My best friend, who was of Italian descent, was Jackie Robinson – because he was the fastest of us. Honestly don’t think we even knew Jackie was a black man. Not sure we would have cared.

“1955 was a magic year for the Dodgers and I was a fanatic afterwards until the ’58 season when they moved somewhere. Never gave a damn about them after that.

“Also got hooked on collecting cards in 1955, mainly to play the game where kids flipped cards against walls. Did that game even have a name? I do remember that the 1955 Koufax was the dregs of the ’55 Topps set. Who the hell was the guy? When you got a Koufax in a pack, you put it with your flipping cards. I even remember a fight between two kids because one of them was flipping too many Koufaxes. Sure would like to have a few of those today. They’d go in a different pile.

“Gilliam (the endorsed store model glove) is indeed a tough ’55 Dodger glove to find. But I lucked into one early on when I was almost totally ignorant about collecting gloves. Toughest for me, other than the Jackies, which I also lucked into, were Newcombe and, especially, Amoros, who I think is the toughest of the ‘55s other than Jackie). I bought the only two Amoros (gloves) I ever saw. It’s a kids’ glove. Absolute piece of cheap junk – could not have sold for more than a buck.

“Biggest Dodger glove regret is passing on a beautiful, high-end, mint Jack Banta from the big Kansas glove find. I had just started collecting and I had no clue that I’d likely never see one again. A quarter of century later and I still haven’t. Never even heard about another.”

Gray was also an ardent glove hobbyist and would track down, if he could find them, the earlier Dodger gloves beginning with Pete Reiser, “Dazzy” Vance, Billy Herman, Cookie Lavagetto and Dolph Camilli.

The arrival of black players into the league created issues not only for baseball sponsors as to if and how to feature Negro players and this thorny problem spilled over into the baseball equipment world where played endorsement on gloves and bats played an important role in their sales.

Major companies like Spalding, Rawlings, Wilson and MacGregor Goldsmith had to approach the possible marketing idea to capture the star power of the emerging black stars.

Rawlings, a company long dominant in the major league player use of gloves, and a leading company name, well respected in the retail glove world, seemed to favor its home town players at this time like Marty Marion with his “Mr. Shortstop” glove and the iconic Stan Musial which propped hefty glove sales. Spalding player endorsements featured many of the New York Yankees, beginning with Babe Ruth but continuing through Joe DiMaggio, Bill Dickey and later Yogi Berra, Phil Rizzuto and Whitey Ford.

The most amazing coup in glove endorsement history though was scored by Rawlings in the signing of one of baseball’s most famous identifiable stars that exists through today, that of Mickey Mantle.

Where did that leave the Dodgers?

The major companies like Spalding and Rawlings seemed reluctant to enroll black players though Campanella would eventually sign with Wilson and have his name on its shelf-model catcher’s mitts.

Taking on the risky marketing proposition and lead of getting black player endorsements would be the MacGregor glove company in Cincinnati by signing Willie Mays, Hank Aaron and Frank Robinson.

Some of the Dodger emerging stars like Hodges, who endorsed with Wilson Sporting Goods, and Snider who joined with Rawlings, having their names stamped on those companies’ store model gloves.

It would take two of the less-known glove maker entities to sign and feature the most of the Dodgers: the Chicago-based Dubow Company and the tiny Nocona Athletic Goods, stuck out in rural North Texas.

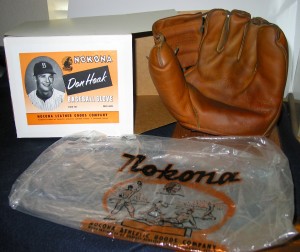

Nokona’s owner Bob Storey, knowing that financially he was shut out of getting big name endorsements because of the prohibitive cost, used a back door approach starting from the bottom up. He would sign players while they were still in the minor leagues and hope they might become big- league stars.

Storey linked a great connection with Brooklyn Dodger farm club manager Bobby Bragan, manager of the Fort Worth Cats, Many of the Dodger regulars and role players would siphon through the Cats in the late 1940s and early 1950s and Bragan made sure these Dodger farmhand would get a tour of the nearby Nocona glove plant where Storey would ink them to a contract.

Familiar Dodgers notables like Erskine, Billy Loes, Bob Milliken, Karl Spooner and even future Hall of Famer Dick Williams would have their facsimile autographs on Nokona gloves also those of course of Bragan, Cal Abrams and Don Hoak to name a few memorable names.

The last family member Larry Dubow in an interview years ago, remembers the Dodger players coming into his father’s plant and his getting their autographs on baseballs. “Sadly I played with all those baseballs,” he recalled.

But Dodger players abounded on the Dubow store gloves: Reese, Billy Herman, “Cookie” Lavagetto, Dolph Camilli, Mickey Owen, Ransom Jackson, “Preacher” Roe, Pete Reiser, Billy Cox, Ralph Branca, Furillo, Newcombe, even Snider and Hodges until they switched their endorsement. The most prominent of these however was the glove signature of Jackie Robinson’s, though only a few of his Dubow gloves seemed to have survived. Sadly most of these Dubow Dodger player gloves are rare. Besides Robinson it’s difficult to find those of the rest of those Dodgers too as Dubow simply didn’t have the mass marketing abilities of the major companies and many of those glove were and are sought by Dodger team glove collectors.

Thanks for the endearing history and charm of the Dodgers lore. I was a youngster,(6yrs old), when the Dodgers left Flatbush but can remember being on my Uncles roof while they listened to the game and had a glimpse of the field from his home on Sullivan Pl. I really only remember being on the roof but the Brooklyn Dodgers were implanted in my bloodline and remain to this day.